Books read, early July

Jul. 16th, 2025 02:24 pmA. S. Byatt, Still Life. Reread. I freely acknowledge that "4, 1, 2, 3" is an eccentric reread order for this series. (This is 2. Stay tuned for 3 in the next fortnight's book list.) It's also the one that, in my opinion, stands least well alone, mostly because of the ending. The ending is very cogent about the initial blurred, horrible phases of grief, but what it does not do is move through them to the next phases, to what happens after the first shock--which is an odd balancing for one book but fine for part of a larger story. I also find it fascinating that Byatt exists in this book as an authorial "I" in ways that she does not for the other books. "I wrote this word because of that," she will say, and it seems that if the I is not Antonia, it's someone quite close, it's not anything near to a character and not really much like an in-book narrator. It's just...our neighbor Antonia, who makes choices while writing, as one does, as we all do.

Linda Legarde Grover, Onigamiising: Seasons of an Ojibwe Year. If you have a relative who is a person of goodwill but has been paying absolutely no attention to Native/First Nations culture, this might be a good thing to give them. It's lots of very short (newspaper column or newsletter length) essays about personal memories and cultural memories through the turning of the year, nothing particularly deep and nothing that assumes that you know literally the first thing about Onigamiising (Duluth) or Ojibwe life or anything at all really. Not probably going to be very memorable if you do, but not offensive.

Alix E. Harrow, The Everlasting. Discussed elsewhere.

Reginald Hill, Death Comes for the Fat Man, Midnight Fugue, and The Price of Butcher's Meat. Rereads. And here we're at the end of the series, and as always I wish there was more and am glad there's this much. I don't think I'll need to return to The Price of Butcher's Meat; the email format conceit ("this is a person who doesn't use apostrophes, that means it's informal!" Reg stop) does not improve with time, and the rest of the book isn't really worth it to me. But the others are still quite solid mysteries, hurrah for Dalziel interiority.

Grady Hillhouse, Engineering in Plain Sight: An Illustrated Field Guide to the Constructed Environment. I picked this up because it was already in the house, and because I'm writing a thing about a city planner, and I thought it might spark ideas. It did not: it's very focused on the immediate 21st century American largely urban constructed environment. But what a neat book to be able to give a bright 10yo, or really anyone who can read full text but likes careful pictures of what there is and how it works.

Naomi Mitchison, Among You Taking Notes: The Wartime Diary of Naomi Mitchison. Kindle. I found this to be a heartening read because Mitchison is clearly a person like us, someone who values art and human rights and a number of good things like that, a person who is doing the best she can in an internationally stressful time--and also she's flat-out wrong a number of times in this book. A few times she's morally wrong, several times she's wrong in her predictions...and the Allies still won WWII and Mitchison herself still wrote a great many things worth reading. It is simultaneously a very friendly and domestic diary from someone Getting Through It All and a reminder that perfection is not required for progress.

Malka Older, The Potency of Ungovernable Impulses. More Mossa and Pleiti mystery adventures. The two spend a large chunk of the book in different locations. Don't start with this one, start with the first one, but also: events continue to ramify and unfold, hurrah events.

Deanna Raybourn, Kills Well With Others. The sequel to the previous "older women assassins attempting with not a great deal of success to be retired from killin' folks" book, it has similar appeal. It could be that you're ready to be done after one, which is valid, but if you weren't, this is more of that, and reasonably enjoyable. There's less of the dual timeline narrative here, about which I have mixed feelings: on the one hand it's often good for authors to let go of that kind of device when it has served its purpose, and on the other I liked the contrast. Ah well.

Cameron Reed, What We Are Seeking. Discussed elsewhere.

Tom Sancton, Sweet Land of Liberty: America in the Mind of the French Left, 1848-1871. This is not just about what people thought of the US at the time but also how they used images and references to it in their own internal propaganda, which is kind of cool. A lot of it was not particularly deep thought, and that is of itself interesting--in what ways do people react to large dramatic events for which they have limited context (but no small amount of possible personal use). If you like this sort of thing this is the sort of thing you'll like. A few eccentric views of, for example, Susan B. Anthony, or the Buchanan presidency, but within the scope of what one would expect for a few lines from someone whose main expertise is not those things.

Leonie Swann, Big Bad Wool. This is the sequel to Three Bags Full, and it is another sheep-centered mystery novel that stays in semi-realistic sheep perspective (except in the places where it goes into goat perspective this time! there are goats!). If you had fun with the first one, this will also be fun; if not, probably start with the first one, because it does have references to prior events. I really appreciate the sheep having sheep-centered theories, it's a good exercise in perspective.

Nghi Vo, A Mouthful of Dust. Discussed elsewhere.

Faith Wallis, ed., Medieval Medicine: A Reader. This is a compendium of translated documents from the period, with very small amounts of commentary between for context. If you want to know how to examine a patient's urine or what humors linen enhances, this is the book for you. Also if you want a window into how people thought of bodies and health over this long and diverse period. I think it's probably going to be more useful to have as a reference than to read straight through, but I did in fact read the whole thing this once (which I hope will help with my sense of what to check back on when using it as a reference).

Martha Wells, Queen Demon. Discussed elsewhere.

Old-timey regency romances

Jul. 16th, 2025 10:23 amI used to collect these in my late teens, once I'd gone through everything the library had. They were sold by the bunch in used book stores, fifty cents for ten, which suited my babysitting budget--I could read one a night once the kids were asleep.

I did a cull of these beat-up, yellowing volumes with godawful covers 25-30 years ago, donating the real stinkers* and keeping a slew of others because my teenage daughter had by then discovered them.

But she left them all behind--she stopped reading fiction altogether around 2000--and I always meant to do a more severe cull, perhaps dump the entirety. But thought I oughht to at least check them out first, yet kept putting it off until recently. While I was recovering from that nasty dose of flu seemed the perfect time.

I finished last night.

Of course most of them are heavily influenced by Georgette Heyer, or at least in conversation with. Some were written when Heyer was still going strong. Authors from UK, USA, Australia, etc. For the most part you could tell the UK ones not only because the language was closer to early nineteenth century--these writers surely had grown up reading old books, as had Heyer--but their depictions of small towns in GB were way more authentic than those written by writers who'd never seen the islands.

But there were common threads. Good things, as one reviewer trumpeted: they wrote in complete sentences! They knew the difference between "lie" and "lay"! In the best of them, characters had actual conversations. Even witty ones! (There's an entire chapter in Austen's Emma, when we meet Mrs. Elton, which demonstrates what was and what wasn't "good conversation." I can imagine readers back then chuckling all the way through at Mrs. Elton's egregious vigor in bad conversational manners.)

But those are the superficials. What about the plots? Here were common tropes shared with contemporary romances of sixties and seventies. A bunch of these tropes have long since worn out their welcome. I didn't know why I hadn't culled some of the books containing the most egregious examples--maybe they were just so common that they were invisible, and there was some other aspect of a given book that had made me chuckle fifty years ago.

Dunno. But in this cull, as soon as I hit the evil aging mistress who will do anything to hang onto the (total jerk) hero, including setting the young and pure heroine up for rape and ruin (which she always j-u-s-t escapes), out it went, the rest of the novel unread: the plot-armored heroine will get her HEA. my sympathy lies with the mistress, whose grim situation veers closer to historical accuracy. Ditto I dumped unfinished the ones where the hero, who can't seem to control his raging hormones (or you know, talk like an adult) mistakes the pure and innocent heroine for a lightskirt and corners her at every opportunity for "can't-say-no" making out, while she castigates herself afterward, moaning, "Whatever is wrong with me?" Basically, while these heroines (and their readers) did not want to be raped, they did want to be ravished. And they weren't guilty of being bad girls if they were overpowered, right?

That was a VERY common trope in the early contemporary romances, the ones read by my mom by the literal sackful, and traded with other women at the local shop. In the seventies, Mom and her buddies organized themselves. None had the budgets to read everything coming out, so one woman would buy the new books from the Dell line, and another the Kensington line, and so on, then they'd trade them back and forth. Mom saved a sackful for my visits--she thought they were something we had in common, and I never disabused her of this, though I was fast getting sick of the "virginity" plotline. I read them all, noting patterns.

I could say a lot about why I think Mom and her buddies couldn't get enough of that plotline, but I'm trying to get through these regencies. In which the authors did understand the social cost of straying. But the heroine gets her reward at the (abrupt, usually) end, a ring from the guy who'd been cornering her for bruising kisses two chapters ago, and wedding bells in the distance. As I got older, I wondered if those marriages would make it much past the wedding trip. As a teen, I read uncritically for the Cinderella story--as I recollect all the weirdness about the heroines and their main commodity, their virginity (and their beauty) whizzed right over my head.

That said. Every so often you'd get a storyline that was a real comedy of manners, and while the research/worldbuilding was never as period-consistent as Heyer's secondary universe, they'd be fun stories. Like Joan Smith's Endure My Heart, which I'd remembered fondly for the battle of wits between hero and heroine--she the secret leader of a smuggling ring, and he the inspector sent to nab whoever was running that successful venture. Now, on rereading it, there were plenty of warts, but I remember the fun of the early read--and the only two attempted rape scenes were done by a villain, not the hero.

The regency romance has staying power, but it's evolved over the decades since these "old-timey" regencies for the 21st C reader who wants on-page sex, without real consequences. And only vague vestiges of the manners of the time. Few, or no, conversations or even awareness of the dynamics of salon socializing. Basically modern women in sexy silk gowns, and guys in tight pants and colorful jackets and rakish hats, with all the cool trappings--country houses, carriages, balls, and the elegant fantasy of the haut monde.

In the donation box the old ones go.

*I'll never forget the one that had to have been written in the mid-seventies, which had the pouting heroine stating on the first page that she was bored, bored, bored with Almack's and why did she have to participate in the marriage mart anyway? She wanted, and I quote from memory, "actualize her personhood!" Then there was the one that featured the hero, leader of fashion, sporting a crew cut and a "suit of flowing silk of lime green"--I think the author meant a leisure suit.

Then there was Barbara Cartland. Whether or not she hired a stable of writers to churn these out once a month under her name or not, she boiled the story down to the barest skeleton of tropes, padded out mostly by ellipses. Except for one early one, published in the thirties or early forties that lifted huge chunks of a Heyer, stuffed into a really weird plot...

Wednesday has socialised enjoyably

Jul. 16th, 2025 07:35 pmWhat I read

Finished Long Island Compromise, and okay, didn't quite go where I was expecting but didn't pull a really amazing twist either.

Alison Espach, The Wedding People (2024), which somebody seemed enthusiastic about somewhere on social media while mentioning it was at 99p. Well, I am always there for Women's Midlife Narratives but this struck me as a bit over-confected plotwise and I was not entirely there for that ending.

Latest Literary Review (with, I may as well repeat, My Letter About Rebecca West).

Simon Brett, Major Bricket and the Circus Corpse (The Major Bricket Mysteries #1) - Simon Brett is definitely hit and miss for me and some of his more recent series have been on the 'miss' side, come back Charles Paris or the ladies of Fethering. But this one, if not quite in the Paris class, was at least readable.

On the go

I have got a fair way in to Jonny Sweet, The Kellerby Code (2024) but I'm really bogging down. It's an old old story (didn't R Rendell as B Vine do a version of this) and for someone who cites the lineage Sweet does, his prose is horribly overwrought.

I started Rev Richard Coles, Murder at the Monastery (Canon Clement #3) (2024) but found the first few chapter v clunky somehow.

Finally picked up Selina Hastings, Sybille Bedford: An Appetite for Life (2020), which is on the whole v good. Okay, blooper over whether Sybille could have become a barrister: hello, the date is post Sex Disqualification Removal Act and I suspect Helena Normanton had already been called to the bar. However, the actual practicalities might well have presented difficulties. And wow, weren't her circles seething with lady-loving-ladies? And such emotional complications and partner changes! there's no 'quiet spinster couple keeping chickens/breeding dachshunds' about what was going on. Okay, usually conducted with a fair amount of discretion and probably lack of visibility, though even so.

Helen Garner, This House of Grief (2014), which I actually started a couple of weeks ago at least, and picked up again for train reading today, as the Bedford bio is a large hardback.

Up next

I am very much in anticipation of the arrival of Sally Smith, A Case of Life and Limb (The Trials of Gabriel Ward Book 2)

Jo Walton’s Reading List: June 2025

Jul. 16th, 2025 06:00 pmJo Walton’s Reading List: June 2025

Published on July 16, 2025

June was a terrific month, I started at home in Montreal for Scintillation, then towards the end of the month flew to Sweden to take a boat to the Åland islands in Finland for Archipelacon 2, this year’s Eurocon. I saw lots of friends and was on a bunch of interesting panels, and it was just terrific. I read thirteen very assorted books, and they were mostly great too.

The Space Between Worlds — Micaiah Johnson (2020)

This is a very odd book. It’s SF set after an apocalypse and it’s about people who can travel to alternate universes, but only those where their alternate selves are dead. You know how some books are vast sweeps of epic and others are intricate miniatures painted with a tiny brush? This is the latter. It’s interested in only two towns (the rest of the post-apocalyptic future world essentially doesn’t exist) and in a very small number of people, though in multiple versions of all of them. It’s very, very good, at the scale it’s working on, but it’s an intimate scale that’s unusual for SF, and which sometimes runs into oddities with genre expectations. It’s slightly claustrophobic, but memorable and effective and very compellingly written. I won’t be reading the sequel, I’ve definitely had enough of this world and these people, but I will be looking out for what Johnson does next.

Olive in Italy — Moray Dalton (1909)

I’m familiar with Dalton as a writer of cosy mysteries, but this is a book about a girl without family going to Italy and, to my surprise, having a thoroughly bad time. This is free on Gutenberg but I can’t recommend it, it’s depressing and just not very interesting.

The Secret of Chimneys — Agatha Christie (1925)

Technically a re-read because I read all of these when I was a kid, but I didn’t remember it at all. A country house, love letters used for blackmail, any number of murdered bodies… it’s all nonsense of course, full of the ridiculous implausibility Christie does so well, and this early in her career she took it more seriously and doesn’t leave any dangling loose ends. Not a good book, but a fun read.

Ragged Maps — Ian R. MacLeod (2023)

Another stellar collection of short stories from Ian MacLeod, who is a terrific writer with the enviable ability to take an SF idea, work out the secondary and tertiary implications, and apply it to real characters living in the interesting world he’s come up with. I’d read some of these before but read them again with pleasure, and others were new to me and very good. MacLeod is one of our best writers, and we should pay attention to him.

Bath Tangle — Georgette Heyer (1925)

Re-read, bath book, and also a Bath book, so that amused me. This is a piece of froth, in which people move to Bath, take the waters, and get engaged to the wrong people. It all comes out in the end like a well-done sudoku. Not Heyer’s very best, but readable and fun, and the characters have very sympathetic problems.

What You Are Looking For Is in the Library — Michiko Aoyama (2021, English translation by Alison Watts published 2023)

A Japanese light novel which is technically genre, but only just. This is a short collection of charming stories about people who have problems that are solved by a (possibly) magical librarian giving them a book they didn’t know they wanted along with a felted creature that she’s made. This sounds more simplistic than it is—it’s actually a lovely window into another culture’s expectations about everyday life. The term “light novel” can be a bit vague, but the books are generally aimed at a younger audience, and many are originally published in frequently used kanji, and thus easier to read. I enjoyed this a lot and I think others might too.

Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information Before the Modern Age — Ann M. Blair (2010)

Before 1550, it was possible to read everything if you worked at it; after that, there was just too much, and people started to write books about what to read and making books of extracts and encyclopedias, and there was a lot of anxiety around all of this. Fascinating book about the different systems people tried in an attempt to keep track of all the knowledge. They invented things we still use like footnotes and tabs and indexes, and also weird things like patent cabinets in which you put extracts on different layers with mnemonics for finding them again. Nobody now would think they could know everything, though there was a time in the recent past when I thought we knew how to find everything. I hadn’t really thought there was ever a time when you could read all the books—and in fact you couldn’t, because they weren’t counting things in languages other than Latin; they were barely thinking about Arabic, never mind Chinese. Blair has a chapter on the world outside Europe that’s very interesting, but her focus here is Europe and the changing perspectives on what a person can know. Great book, readable and interesting and does not require any prior knowledge of anything.

The Husbands — Holly Gramazio (2024)

Re-read, book club, and we had a really great book club discussing it. I hadn’t meant to re-read it, as I’d read it fairly recently, but after opening it up to remind myself, I found I was halfway through it before I noticed. Extremely readable book about a woman who isn’t married in her original life but finds husbands she might have married in alternate worlds coming down out of her attic, and vanishing again to be replaced by another if she sends them back up. The book rings the changes on this theme extremely well, in a thoughtful and excellent way. It’s an interesting contrast to The Space Between Worlds because that too is about alternate worlds and just a few characters, but here we have a very wide cast of husbands, and the wider world isn’t affected at all.

The Humble Administrator’s Garden — Vikram Seth (1985)

An early book of poems by Seth, finally available as an ebook, and just as delightful and unexpected as all his poetry. Highly recommended if you enjoy poetry at all.

Harvard Classics Volume 33: Voyages and Travel — edited by Charles W. Eliot (1909)

I’ve been reading my way through the Harvard classics volume for a long time now, and this one is odd. It’s the part of Herodotus about Egypt, part of Tacitus’ Germania, and bits of voyages of Drake and Raleigh. All of it was enjoyable, none of it was a whole book, it did not feel connected in any rational way. I guess the theme was like the Le Guin story where aliens ask to be told about Earth and the ambassador just tells them about Venice—there is a whole planet, humans have been on it for a while, you can’t see all of it at once, but here are some angles.

Camp Concentration — Thomas M. Disch (1967)

Re-read, for book club. This is a grim book, and it didn’t feel any less grim on this re-read. The theme of increasing intelligence must have been in the air, as Flowers for Algernon came out the year before in novel form. Perhaps this was a response to the novella? A vain poet and conscientious objector in a future war finds himself part of an intelligence increasing experiment. Brilliantly written in full New Wave style, and not very long. None of the characters is sympathetic, and it has aged oddly, some of it feeling more relevant than when it was written, other parts being things nobody would write now. Read it, but brace yourself. Again, this led to a very good book club discussion.

Mrs Tim of the Regiment — D.E. Stevenson (1932)

I’d previously read the second book in this series. This is much less good. Hester is married to Tim, he’s in a regiment, she has to move around because of his job, they have two children, and servants, and have to move to Scotland… and then in the second half, Hester is staying with a friend in the Highlands and two men are in love with her and she doesn’t notice. The resolution—or what would be the resolution in the love story the book keeps threatening to turn into—is averted. Hester herself, whose diary the book purports to be, is a good point of view for understanding some things and not others, and the story is not without charm, but the whole book is unbalanced and doesn’t quite work. Stevenson has written much better.

Revolutionary Spring: Europe Aflame and the Fight for a New World, 1848-1849 — Christopher Clark (2023)

This is a very long and detailed book about the revolutionary uprisings of 1848 and why they both did and didn’t change the world. They didn’t become the revolution people expected, but they changed regimes in many places, and had long-lasting effects. This is a book full of details that also constantly pulls back to look at the big picture, with the effect of speedy communications meaning that, for instance, events in Paris affected those in Hungary and vice versa, even when the people weren’t in touch at all except by reading newspapers about what was going on. It’s a really fascinating time, and this is an excellent account and reflection.

[end-mark]

The post Jo Walton’s Reading List: June 2025 appeared first on Reactor.

Hacking Trains

Jul. 16th, 2025 04:57 pmSeems like an old system system that predates any care about security:

The flaw has to do with the protocol used in a train system known as the End-of-Train and Head-of-Train. A Flashing Rear End Device (FRED), also known as an End-of-Train (EOT) device, is attached to the back of a train and sends data via radio signals to a corresponding device in the locomotive called the Head-of-Train (HOT). Commands can also be sent to the FRED to apply the brakes at the rear of the train.

These devices were first installed in the 1980s as a replacement for caboose cars, and unfortunately, they lack encryption and authentication protocols. Instead, the current system uses data packets sent between the front and back of a train that include a simple BCH checksum to detect errors or interference. But now, the CISA is warning that someone using a software-defined radio could potentially send fake data packets and interfere with train operations.

Don’t Put That Thing in Your Mouth, Either: Ben Peek’s “Edgar Addison, the Author of Dévorer (1862-1933)”

Published on July 16, 2025

Share

The Ambiguous Realism of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Lost Trilogy

Jul. 16th, 2025 04:00 pmThe Ambiguous Realism of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Lost Trilogy

Published on July 16, 2025

Something fascists and poets have in common is their awareness that a single sentence can change a person’s mind completely. How does a sentence do that? Poetry and political action are everywhere one looks in Ursula K. Le Guin’s many books, most famously in novels like The Dispossessed and Always Coming Home, but her most radical and covert storytelling hides in a trilogy from the 2000s that largely got lost in the shuffle: The Annals of the Western Shore.

2000-2010 was Le Guin’s busiest publishing decade, and it was from 2000-2002 that she (for the most part) wrapped things up with Earthsea and the Hainish Cycle. Nine other books would come out before the end of the decade. Here’s the rundown.

Since it originally appeared in Asimov’s Science Fiction in 2002, I’ll put the novella The Wild Girls first on the list, even though the PM Press edition came out much later. After that, a collection called Changing Planes appeared. Then came the three novels of this lost trilogy; then the monumental essay collection The Wave in the Mind; then Le Guin’s sixth poetry collection, Incredible Good Fortune; then her final novel, Lavinia; and lastly the charming and acerbic Cheek by Jowl, another essay collection brought out by Aqueduct Press.

The 2000s was that very special time in YA publishing that gave us the great Harry Potter book heist. If there are a few reasons for the trilogy’s relative obscurity then as now, the shadow cast by the Boy Who Lived certainly looms large among them. How could an entirely new fictional universe created by one of SF’s most beloved authors possibly compete with this pop culture juggernaut? Without going too deep into the marketing involved, it will suffice to say that the novels Gifts, Voices, and Powers did win some praise and awards, but did not make the splash one might have expected. Yes, Powers earned Le Guin her sixth Nebula Award (and to give a sense of just how long ago this was, the Ray Bradbury Award that year went to Joss Whedon), but after that, as Le Guin herself later pointed out, the novels were largely ignored. Back in 2009, Jo Walton wrote about the Annals on this very website, covering just about everything that would encourage long-time fans and new readers alike to pick up the books. Like many other long-time Le Guin fans I’ve talked to, I was always curious about these novels, but they languished on my TBR pile for nine years before I finally got them. I had no idea how engrossing and powerful they would be; how relevant, how necessary for the current moment, how truly Le Guinian their telling and knowing.

Unlike the tales of Earthsea and the cosmos of the Hainish cycle—both written over the course of several decades and undergoing along the way a lot of ontological shapeshifting in response to the author’s own growth—the Western Shore, the little coastal realm that is the world of the novels, was hatched and brought into view over the course of just a few years. Its orogenies had no time to spare, didn’t undergo any shattering conceptual reimagination, and so in this sense, as a world, it’s a little less complicated than Earthsea or Hain—and Le Guin wanted it that way.

She was starting fresh, and she tells us that in Powers directly, through its protagonist Gavir:

“Are there more tales like that, Gav?”

“There are a lot of tales,” I said cautiously. I wasn’t eager to start another epic. I felt myself becoming the prisoner of my audience.”

It could be that she was eager. With The Telling, Tales of Earthsea, The Other Wind, and The Birthday of the World all hot off the press by 2001, it isn’t hard to see what this moment in Gavir’s storytelling life meant to the author. In a way, it’s one of the bigger what-ifs of her career: What if I left what I have made, and what has made me, behind? The three protagonists of the trilogy, Orrec in Gifts, Memer in Voices, and Gavir in Powers, all play their part in answering this question. Beneath Earthsea and Hain—and Orsinia and all the rest—is an underlying Le Guinian physics; on the Western Shore, which is unburdened by archmages and NAFAL ships, this physics is plain to see. What you learn becomes what you know and what you know becomes what you do. The rest is either the path of least resistance, or, in some cases, of most resistance.

Before we dive into discussing the novels themselves in detail, we need to start by talking about what we talk about when we talk about YA. Right from the jump it is both relevant and irrelevant to say that these novels, marketed fiercely as YA fiction when they were published, are as much about adults and adulthood as they are young adults and young adulthood. They show us—as Le Guin does so well—that the boundaries between these constructs aren’t often useful or meaningful. Remember Herman Hesse’s YA novels: Peter Camenzind, Gertrude, Beneath the Wheel, Demien? The Annals of the Western Shore are like those, but better.

In 2004, right before Gifts appeared, Le Guin wrote a rather mordant recipe for YA fantasy literature in Time Out New York Kids. “All you need,” she insisted not long before all those copies of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix were stolen from that warehouse, “is a map with weird names.” This indictment of the Fantasy Industrial Complex is not limited to this expansive reductionism, and her feelings about Harry are well enough known that we needn’t get into it too much, but neither can we turn away from it. It stands to reason that some combination of competition and audience perception about YA, both in terms of genre and age group, buried the Annals. Le Guin had spent almost fifty years writing about genre and audience in her essays and talks, and yet the YA fence was just too high for the grownups to climb over.

Some OAs (Old Adults) read YA fiction to chase questions about themselves and the paths they’ve found, or that have found them. Some want writing that is searching and, like themselves at times, reaching. It has been sixteen years since Jo Walton’s article and some of her remarks back then are echoed in today’s discourse about YA: just read a review of Karen Russell’s The Antidote; the persistence of the same set of questions and anxieties is striking.Are Young Adults and Old Adults all that different, the discourse wonders year after year, story after story? Can Young Adults handle tough subjects like death, sex, justice, reality? Can Old Adults? We have learned to call this uncanny proving ground Omelas.

One more thing. Everyone—every person I have talked to about these books who has seen them says the same disparaging thing about the covers, has judged them on that basis. I want to state for the record that it did take a while (I got the books in 2016 and read them in 2025), but I now believe the Graphia/Harcourt covers are perfect. They demand that we see ourselves, our enduring young selves, in the stories and as other people; through that anachronism and embodiment—the reader’s Reading—is liberation, freedom, and, at last, the land of the Sunrise.

Ok, here goes nothing:

Annals of the Western Shore is a tale of three estates: that of Caspromant, that of Galvamand, and that of Arcamand. These estates are far flung across the Western Shore; they are culturally distinct, they are geographically distinct, they are very far away from each other, but they have a lot in common. Born to these estates are the three remarkable young people mentioned above. All three stories are about how the self is discovered, the surprises that come along with the discovery, and what those surprises feel like and mean to ourselves and to our families. All three are about how literacy is an intellectual, spiritual, and political tool, an initiation, that connects people. All three tell the stories of apprentices and masters, mentees and mentors, finish lines and beginning places.

Gifts takes place in the remote Uplands of the Western Shore, in the northeast, and the reader doesn’t come down from them much in the course of the novel. Only through the protagonist’s mother do we hear about Derris Water, the small town closer (though not by much) to what might be called the region’s imperial core. It’s time for young Orrec to come of age, to come into his power, to harness his gift. But there’s a problem. It never happens. In interviews around the time the books were published Le Guin frequently claimed that her inspiration for the giftless child came from an image she had in her mind of a Musicless Bach, a virtuoso with no prowess, no ear. This is a classic Le Guinian thought experiment. The novel tells how Orrec and his family and neighbors navigate the shame and guilt and frustration that surrounds the missing gift—but shows us in the end that he has a different gift: literacy, and specifically the gift of the poet. It is literacy, the gift given to him by his mother’s tutelage, that empowers Orrec to change the Western Shore.

One of the most engrossing aspects of Le Guin’s worldbuilding in the trilogy is the Western Shore’s literature, both classical and contemporary, and the way it shapes social and political life. Le Guin has imagined for this realm its own Horaces and Catulluses, its own Diodoruses, its own Diane di Primas. Perhaps the most famous poet of the Western Shore is Orrec Caspro himself, who famously writes, at some point between Gifts and Voices, “Belief in the lie is the life of the lie.” That’s a powerful sentence, a radicalizing sentence. Characters so intimate with their culture’s literature and stories, like Orrec and Memer and Gavir—for whom literature and poetry are reality—prefigure the conceptual framework of Lavinia, with its main character who is aware of Virgil and its Latium that is Napa.

From the Kesh of Always Coming Home, to the Hernes family in Searoad, the West Coast has for many years been an enduring preoccupation of what might be called Le Guin’s naming-driven autofiction (or autofantasy, really) a Californication of one’s own. As inventive and indeed as alien as her words for these worlds can be, there is also a side—to some of it—that is deeply personal, plain almost, and tied to her upbringing in California, her roots there, her parents. The Western Shore, like the Kargad Lands of The Tombs of Atuan, and like the Klatsand of Searoad, is an imagined West Coast borne of the one the author grew up on and the one that existed before the arrival of white settlers, before the Gold Rush, before Napa Valley, before Joan Didion, and before Hollywood basement science fiction as we know it.

Le Guin has been experimenting with science fiction as we know it and with alternate realities for a long time. Before The Lathe of Heaven, there was her story “Imaginary Countries,” a plainspoken thesis positioned, adroitly, right at the end of Orsinian Tales, behind a fourth wall. As with much of her other work throughout her career, these alternate realities can be traced back to Le Guin’s interest in Austin Tappan Wright’s Islandia and, perhaps as significantly, to the novel’s sequels written by Mark Saxton at a time when conversations about universes and IP were less codified than they are today (those sequels always call to mind Alan Dean Foster’s Dinotopia novels to me).

In Voices, Memer finds herself living across from a holy mountain in a city by the sea that has been either under siege or occupied by an enemy, the Alds, for her entire life. She is in the midst of discovering the true nature of her faith, and she is also in the midst of a succession crisis—right at the moment, in fact, that the enemy is embroiled in a succession crisis of their own. She is surrounded by authority figures: men. Witnessing the power plays of these men on one occasion, she “stood stewing in [her] resentment and not listening to what [they] said, Ioratth and Orrec, the two princes, the tyrant and the poet.” It had been, and would continue to be, the sentences spoken by the two men that decided the fate of the city. One speaks sentences of oppression, the other the sentences of uprising. You will have to read the book to learn what Memer’s sentences do and decide for yourself what they mean. Just as the Delphic epigram twists fate, so too does the call to arms.

Memer also faces misgivings in the course of her own initiation. When the story begins she has recently come to understand that she is part of a mysterious religious group—an ancient one—whose estate in the city hides a secret library that is built over a sacred cave. Some of the voices of Voices are heard in this cave, which is a lot like the caves in The Tombs of Atuan (more on that later). When she first learns to read, an initiation unto itself, she wants books about “fighting the enemies of your people, driving them out of your land.” Living under the oppressive regime of the Alds, in a society where books are forbidden and liberty is only whispered of, literacy swiftly fast-tracks her search for faith and belonging to the mysteries of the cave. It also fast-tracks her understanding of her own oppression, her life as a “siege brat.”

Initiation is an interesting word: it comes from a cluster of Latin words meaning “the beginning,” “to originate,” and “to enter.” It also has a proto-Indo-European root meaning simply “to go” or “going”—an idea at the core of the Tao. The initiation in Voices is pretty different from the ones in the other books, but they are all very much of the Tao. Take a look at this piece of Le Guin’s rendering of Hexagram #15 from her version of the Tao Te Ching:

Who can by stillness, little by little

make what is troubled grow clear?

Who can by movement, little by little

make what is still grow quick?

Very Gavir. It is also, come to think of it, very Orrec and Memer. The protagonists of the Western Shore follow the Way.

At the beginning of Voices a slightly older Orrec finds his way to Memer’s estate and, through the way he chooses to involve and not involve himself in the conflict with the Alds, eventually plays a critical role in the city’s liberation. His arrival is that of a celebrity. At his public performances and at those that he gives in the court of the city’s occupying power, he recites classics and original work and is able to engender by turns the revolutionary spirit in the people of the city and patriotic sentimentality in the Alds. He even—and this happens in all three novels quite symmetrically—successfully endears himself to the city’s sitting authoritarian and sets the collapse of his power in motion, recalling Hexagram #17 of Le Guin’s Tao Te Ching. About an invisible leader, she called this one “Acting Simply.” The last stanza reads:

When the work’s done right,

with no fuss or boasting,

ordinary people say,

Oh, we did it.

Something that might be magical happens in the first scene of Voices; an ambiguously magical gesture; a word written on a wall with the tip of the index finger. It’s a kind of key or password Memer uses to enter the secret library: tracing a word in the air. Curiously, this gesture and its power are unique in the novel; nowhere else are gestures of this kind made or used. It’s almost like a little piece of magical bait Le Guin uses to get us to listen, to trust that traditional magic is part of the story. Elsewhere in the novel we do encounter moments of the fantastical, but none so traditionally “magical” as the key to the library. In fact, other elements of the story that depart from realism could just as easily register as paranormal or supernatural. Since these kinds of experiences and phenomena are reported so ubiquitously in reality, it could be argued that the novel is more or less delivered in a realist mode, the “green country” kind of fantasy Le Guin discussins in Cheek by Jowl, akin to the setting of stories like “Gwilan’s Harp.” Not swords and sandals, exactly; a green country, an imaginary country, an ambiguous realism, a version of her beloved West Coast—a kind of autofantasy borne of the same love of landscape that, as she also notes in Cheek by Jowl, also gave her The Tombs of Atuan:

“[The book] came from a three-day trip to eastern Oregon: the high desert, the high, dry, bony, stony, sagebrush and juniper country… I knew I was in love and had a book. The landscape gave it to me. It gave me Tenar and where she lived.”

As we know, Tenar came with more than sagebrush and juniper. She came with death and those voices of death that are, mostly but not absolutely, issued from a terrestrial (debatable) and subterranean mouth. We meet another Tenar figure and listen to another mouth in Voices. This mouth has a supernatural inflection, but it is a realist mouth. Hexagram 58, “Living With Change,” reads:

The normal changes into the monstrous,

the fortunate into the unfortunate,

and our bewilderment

goes on and on.

On the map Le Guin drew of the Western Shore, between the Morr River and the Bay of Bendile, lie the Marshes and their finger lakes, where, in Powers, Gavir and his sister were born and kidnapped. The echo of the Awhari people and the historic marshlands of southern Iraq is unmistakable here and has a certain resonance with a question Le Guin was often asked in interviews about the Annals: were these stories inspired by the war in Iraq? She always said no. It’s hard not to think of Tolkien while reading this section, recalling the textures of the world he knew instantiated in Middle-earth—and the discourse that surrounds such gestures. Curiously, at the very end of Voices, we learn—is it some kind of Easter egg?—that the voice in the cave is called “The Lord of the Springs.”

Gavir’s story is about the awakening of class consciousness and a quest for trusting relationships—how’s that for fantasy? He learns the hard way, as so many of us have, that the road to liberation is paved with aggrandizers. “The pace of oppression outstrips our ability to understand it,” Karis Nemik tells us in Season 1 of Andor. What do those things mean to our professions, vocations, avocations, families, chosen families, and selves? There is too vast a cast of characters to talk about it all here, but from the unmistakably Gollum-esque Cuga (whose mind-changing sentence was a joke well played), to the charismatic aggrandizer Barna, himself a kind of dark Tom Bombadil, we get a little bit of everything Le Guin has always loved and warned us against. Our ambiguous utopia is The Heart of the Forest. A sinister avatar follows the protagonist like a ringwraith. In another echo of Tolkien this wraith is thwarted by a rushing river. Self-styled radicals roam wooded glens, backwoods patriarchs compete for the most life-threatening alcohol poisoning—and the women add the real world to their baskets of leeks and do all the heavy lifting that goes unseen, indeed unconceived of by hero (if they exist) and villain (if they exist) alike. The Alehouse Chronicles. The Annals of a Failed Planned Community.

“Annal” and “chronicle” are fantasy-coded terms; recall how some editions of Searoad have the subtitle “Chronicles of Klatsand.” The Annals’ ambiguous fantasy in fact very purposefully avoids fantasy, subverts it. In a short essay about John Galt’s Annals of the Parish, Le Guin explains that “small-town novels are intensely grounded; rich in satire, humor, and character, human affectations and affections. Intimate knowledge of one small community may yield psychological and anthropological insights of universal value.” As the characters of the trilogy rove and wander across the Western Shore, from its Uplands to its City States to its Marshes, Le Guin puts this small-town novel framework to the test, and in so doing creates a deeply real, familiar and human realm out of a map with weird names. One scene from Parish Le Guin wrote about having enjoyed finds its way into Powers in a scene about Gavir eating dinner with the man he’s just found out is his uncle. After a day—a lifetime—of soul-searching, grief, and existential dilemmas, some fishcakes and ricegrass wine will cure what ails you, make fantasy reality, or reality fantasy, whichever one gets the point across if there is one.

So at the center of fantasy is magic but there is no magic on the Western Shore—perhaps—and the word is almost never used. Enchantments are not woven, spells are not cast, curses are not visited upon nor lifted from victims. There are no dragons or oliphaunts or Lambs of Tartary, no Greek fire, and no wands. The closest thing we get to a mythical beast is a “halflion,” a very apt symbol for the kind of fantasy we’re dealing with; a realism-inflected, terrestrial, domesticated, behaviorally sentient and certainly compliant hybrid organism. Her name, of course, is Shetar.

Instead of magic, the word “gift” and the word “power” are used more or less interchangeably, and the one is used to describe the other, depending on who’s talking or thinking. Gift, strictly speaking, is an Uplander word for one of a variety of special abilities, for example the calling, or the twisting, or the undoing. These are hereditary. Both words are also used to describe a person’s craft, their talents and special skills—and can also be hereditary (“he gets it from his mother”). For example, Gavir’s gifts (or are they powers?) are the gift of the angler—here we are, firmly rooted in reality—and the gift of the oracle. He also has what sounds like an eidetic memory.

Here we enter rather thorny territory: the function of magic in literature versus the function of magic in reality. Oracles, such as the famous one at Delphi, are factually real, since they exist and are part of history. Ordinary people claim to see the future, the past, beyond the veil, every day; the world has plenty of these traditions, woven into the fabric of myriad ancient and modern cultures. On the other hand, some people win Jeopardy! night after night without aid, and the existence of eidetic memory itself is still doubted by some. It is curious, since so many share the word, that definitions of magic tend toward the ideological, away from consensus.

So, is being able to see the future a gift, a power, “magical” at all? Is it not real? Characters sometimes talk of spells, witches, and wizardry but always in the context of superstition. And this is all to say that magic may not be what we are dealing with on the Western Shore. The gifts and powers we encounter—of the supernatural kind—aren’t so extraordinary that they couldn’t be explained away by Dana Scully, and in fact the Western Shore has its own Agent Scully, Venne, in Powers. “A whip and a couple of big dogs can do about as well as a spell of magic to destroy a man,” he states—a prosaic if grim explanation. Venne would agree that giftless, unmagical people kill others quickly and slowly, set fires, and devise cunning means of attracting prey. Giftless, unmagical people do not need magic to kill expeditiously, to make fire, or spread disease; we see the evidence every day on our phones; their imaginations and technologies aid in the perpetration of those harms well enough without the supernatural. That being said, the people of the Uplands and the wider Western Shore generally talk about the gifts in terms of use—value and social power: so it’s practical magic to them and breathing air to us, a matter of realist talent, the magic of the virtuoso or the savant. But not everyone on the Western Shore thinks that way, to say nothing of the schisms here on Earth.

By the time we’ve travelled from The Uplands, to Ansul, to the Daneran Forest, to the Marshes, a certain universal local exceptionalism amongst communities becomes apparent. These gifts we keep hearing about aren’t unique to the strange hill people, or the strange city people, or the strange marsh people. The gifts, whatever they are and whatever their differences, are everywhere. They are, in fact, quite commonplace. Traits, perhaps.

So one person’s magic is another person’s garden-variety psychokinesis. One person’s incorporeal non-human intelligence in a cave that exerts authority and influence over a small group of believers is another person’s Ancestor. One person’s prognostication aided at one point, ceremonially, by entheogens, is another person’s educated guess. The magic word written on the wall: it’s a doorcode. It’s your conscience speaking, it’s your intellect speaking. Sometimes, as our heroes all learn, the solution you synthesize is smarter than you are and makes you smarter than you were. It’s a leap, a revelation, a eureka moment. That’s not magic, or a literal ancestor literally speaking through you—but the throughline of thought is close to being literal because it’s brought about by pedagogy, tutelage, and apprenticeship: learning.

Stories and claims about the paranormal abound on Earth, but we don’t live in a fantasy-reality do we? On Earth, ancestors are real, the mind is real, and the will endows cause and effect with the narrative verve we see and feel all around us. In this sense the Annals of the Western Shore is solemnly realist, not debatably fabulist—not that Le Guin would give a halflion shit what we call it beyond the plain fact that it is made up of three novels. In Cheek by Jowl, she defines novels as “stories about starting and sustaining chain reactions of mistakes”—mistakes, their ramifications, and how those ramifications are managed by the people involved. Recall that a ramification in the broadest sense is a branched structure. Le Guin has often warned that rationality cannot always help us. Rationality is a pretty fraught concept because of its tendency to fail us right when we need it most. It doesn’t make sense, but, as we hear so often, “I know what I saw.”

These problems recall another novel that appeared just before Annals: The Telling. The Telling is telling. It’s a Hainish novel, but a few little changes would make it a standalone…or a Western Shore novel for that matter. The story itself is standard-issue Le Guin: struggle, oppression, regime, an old world in a state of elegy, a hidden library. And at the center of it is something that can’t be explained that looks an awful lot like magic, or the supernatural, or the paranormal, but we don’t ever find out what it is. All we know is it can’t be made sense of empirically or rationally. Or can it?

So if rationality can’t help, and more broadly that which is scientific and empirical, and if magic and metaphysics and other weird stuff also can’t help us, what exactly is left in our quiver? What remote reach of fantasy are we working with here? Where—she would probably roll her eyes—did this fantasy framework come from? To answer that, we need to talk more about the history of California and her mother’s famous and controversial book, Ishi in Two Worlds. And her father a little bit, as well.

The easiest way into this is through Le Guin’s essay “Indian Uncles,” which Le Guin originally wrote as a talk in 1991, and then revised in 2001, a few years before Gifts was published. She included the essay in her 2004 collection The Wave in the Mind, and “Indian Uncles” very well may have been a wave in the mind splashing on the Western Shore. In this essay, Le Guin talks about growing up in California, and her parents, Alfred and Theodora Kroeber. She tries to dispel some misconceptions about her own connection to members of California Indigenous groups, and to elaborate on friendships and experiences not widely known. This is important because Indigenous California is part of the fabric of Le Guin’s California. This is certainly overtly expressed through Always Coming Home; it’s a big part of the Annals, too. “Indian Uncles” reminds us that many of Le Guin’s early impressions of Indigenous people, culture, and stories were those of a young child who found herself in the midst of a very specific intellectual milieu. Of course she was not doing then what we call “worldbuilding” now, but bits and pieces of what she learned do seem to have made their way into the concepts and perspectives she would later work with in her fiction.

American anthropologists like Le Guin’s father referred to the once culturally diverse region of Northern California as a “shatter zone,” a populous and intricate mosaic of peoples and languages tightly fitted into a relatively small territory. The uniqueness of this zone has been researched and commented on extensively in recent years, notably by David Graeber and David Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything, and in more granularity by Brian Hayden in The Power of Ritual in Prehistory. With dozens of distinct groups and subgroups, languages and dialects, the region was also of particular interest, famously, to Alfred Kroeber, and much of Theodora’s telling of it in her book Ishi in Two Worlds is devoted to exposing the atrocities committed there by outsiders. The unattainability of total obliteration and assimilation is a common colonial failure, a phenomenon keenly observed, known, felt, and ultimately exploited by Memer and her friends in their resistance to the Alds in Voices, but it is mostly in Powers that we hear echoes of pre-colonial California, and mostly in Gifts that we hear echoes of Theodora’s work.

Growing up with Kroeber as a father, whose work has come to be the subject of much debate, and was done in proximity to other legendary ethnographers like Jaime de Angulo, Le Guin’s early existence was redolent with information and ideas about the history of the region that would take decades to reach the wider public. She tells us in “Indian Uncles” and elsewhere that the person who helped contextualize this history early on was her mother. Theodora wrote a number of books based on California Indigenous groups and their stories. As with de Angulo and his Pacifica Radio program “Old Time Stories,” Theodora’s interest in Indigenous culture and history centered story and storytelling for her audience. Ishi in Two Worlds, The Inland Whale, and Almost Ancestors (this last title published by the Sierra Club) saw Theodora Kroeber tell and retell a variety of native histories and stories, bringing them not only to the attention of a largely ignorant American public, but to her young daughter, our beloved UKL.

Ishi in Two Worlds was published in 1961. The book is about the last remaining member of the Yahi, and his emergence from the hills of central California into the world of Berkeley Academia on August 29th, 1911. Ishi, and the other books, as with her husband’s work, are part of a vast corpus of anthropological and ethnographic literature produced in the 20th century that is always being reevaluated by scholars and historians. Despite being an explicit indictment of white settler colonialism in California and its attendant genocide (“extermination” is the word the author uses), and despite, perhaps, her best efforts, the book, for some, fails to meaningfully tell the whole story of Ishi’s fate.

Where it succeeds, however, is in providing a model for Le Guin’s later speculative enterprises; from the storytelling itself to the hand-drawn maps and illustrations, the leap from Indigenous California to the Western Shore is every bit as clear as the one that landed on the Kesh in Always Coming Home—but there are, of course, big differences, too.

In Ishi in Two Worlds Theodora tells us that the Yana in California “apparently enjoyed recounting their dreams to one another sometimes…They might read a predictive significance in dreams after the fact, but the act of dreaming and recalling of dreams was not systematic with them, nor did it attach to mystic belief except for those dreams in which they got power: the vision dreams. Those were something apart, and private.” This framework is perhaps one or two thought experiments away from Gavir’s narrative arc.

In 1965 Theodora created a version of Ishi for children, which was published by Parnassus Press—the same Parnassus Press that would later commission Ursula to write A Wizard of Earthsea. Like her other books, the new Ishi book was one of retellings. A little bit like in Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun, Annals of the Western Shore contains many tales-within-tales. One of the first ones we hear is from Orrec’s mother, Melle, and resident librarian of Caspromant. One character refers to it as the story about “the girl who was kind to the ants.” It’s a strange story, an old one, about four siblings who embark separately on an identical quest, but only the fourth succeeds because she is Good. Orrec’s mother, forgetting how it ends, improvises a standard comedy wedding ending, which does not go unnoticed. What about the ants? She improvises. Everyone laughs. Improvisation, the story’s versioning, is part of the telling. What does the story mean to different people? Why does it get retold?

Lots of culturally related but distinct groups all living in close proximity to one another in a landscape just as various, on the western shore of a continent, gets us part of the way to Ansul, the Daneran Forest, and the Uplands, but, especially in the case of Powers, it is one specific cultural difference that draws a clear line from the “shatter zone” and the Pacific Northwest to the City States of the trilogy, and that is the institution, in the City States of the Western Shore, of slavery.

In The Dawn of Everything, the Davids explain how the institution of slavery is thought to have functioned amongst some Indigenous groups of the Pacific Northwest, and draw rigorous distinctions between their speculations and what is known about other instances of slavery in history, from antiquity to the Caribbean to the United States. Their analysis, which is rooted in a Chetco tale retold by A.W. Chase in 1873, evinces that “the rejection of slavery among groups in the region between California and the Northwest Coast had strong ethical and political dimensions,” in a way that is especially hard to miss in Powers, but that reverberates through the whole trilogy. Many characters in the book, major and minor, from the Uplands to the Carrantages to Mount Sul, share their own definitions of slavery, captivity, and oppression, and the regions of Western Shore in which the institution of slavery is present, and those where it is not present, are clearly known to everyone.

A key term used in The Dawn of Everything’s breakdown of all this, one that is a bit academic but really useful, is “schismogenesis”: a phenomenon in which cultural groups define themselves by being unlike their neighbors, and this becomes baked into cultural identity as well as value systems. On the Western Shore we see this happening not only between regions and city states, but even on the much smaller scale of the villages that make up the Marshes, the domains of the Uplands, the great Houses of Etra. Shared language, yes, shared customs, yes–but the people on the other side of the lake, across the field or across the street, are not like us. This is all to say that the schismogenesis framework for pre-colonial California maps neatly over the Western Shore.

The Annals of the Western Shore and the lives of its inhabitants are filled with crises, upwellings of isolation, moments of humility and grace, moments of confusion and violence. At the heart of it all is the yearning its people have for trust and the power it takes to secure that trust. There are powers that connect us and powers that can cut us all off from each other. Le Guin called her Hexagram #49 “Trust and Power.” She says of the wise amongst us, for whom “power is trust”:

They mingle their life with the world,

they mix their mind up with the world.

Ordinary people look after them.

Wise souls are children.

Le Guin’s story “Imaginary Countries,” first published by The Harvard Advocate, appeared in 1973, not long after Robert Silverberg first published “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” in New Dimensions 3. In both monumental stories, Le Guin laid down some ground rules that she’d follow in many of her subsequent works. We see them followed thereafter in most of her stuff, from Malafrena to Tehanu, from The Eye of the Heron to the Annals, to her late story “The Jar of Water.”

The story takes place in an estate, too, a summer house called Asgard. The house is situated in an idyllic dell, and family who lives there from June to August all participate in a little mythological make-believe: they visit a giant ersatz Yggdrasil—an ancient oak on the property; the part of Thor is played by the family’s six-year-old daughter. A narrator very much like Gavir does some perceptual time-travelling for us, or perhaps some remote viewing, or perhaps what he does is some good old-fashioned realist thinking—that great gift, that great curse. At the end of the story Le Guin punks us hard—the immediacy we’ve felt has been for the last day of summer in 1935, and its world is gone, if it ever existed at all. What remains of it clings to our cortexes, where it tumbles and metamorphoses, asserting its reality ever more strongly as its details undergo time’s fictionalization. Ragnarok is coming; will the Uprising?

We see this same scenario play out in Powers, when the children of Arcamand build their model of the ancient citadel of Sentas at the family’s summer house, based on a poem they learned in school. The ideal of Sentas and its reconstruction in miniature by the children in Powers, a symbolic place of refuge, ends up being a lot like the Heart of the Forest in that it doesn’t really function, and people can’t really live their lives there. They are both models, proofs of concept, dummy utopias. The children seem to know that, so it’s interesting that the adults in the Forest don’t—or are in denial about it. Of course, we see a lot of denial in these stories, which aspire to realism and relatability in their funny and very successful way. The realism of the poet.

Poets are taught, one way or another, that real power is generated by an economy—of language. Concision and rhetoric cut costs without losing voices. How these currents shape a construction and what it might mean, and how that fits into an attention span, is a matter of conviction—and the differences we’re willing to see between an instrument and a weapon.

Le Guin was more and more outspoken toward the end of her life about values: what they are and why they are lived by and what they are lived for. What is meant by “values”? “Maybe she didn’t know herself, and told the story to find out,” Orrec wonders about Gry early in Gifts. These kinds of intangibles are, after all, what animate our material selves; what lead us into battle and away from our oppressors.

An Old Adult can like and learn from YA, just like a Young Adult can like and learn from OA. It does work both ways in fiction and in life. Comparing the Lexile score of The Dispossessed to Powers (which I did do) is about as useful and generative as comparing the conceptual difficulty—for anyone—of anarchism and grief: not very. No matter how old you are, what year you were born, how precocious you are or how juvenile, you have not and will not master either anarchism or grief. You will die first.

In the meantime, books can help us along the way, especially books like these. How you say something can be a matter of life and death, freedom and oppression, audience and obscurity. Simplicity, compression, the sensation of convincing and of being convinced: there is a rhetorical battle of sentences being fought and it is fortunate that books by writers like Ursula K. Le Guin continue to be discovered and rediscovered, and that their sentences speak on the side of liberty. Read the Annals of the Western Shore—then get out there and write your own.[end-mark]

The post The Ambiguous Realism of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Lost Trilogy appeared first on Reactor.

Aaron Taylor-Johnson Will Star in Robert Eggers’ Werwulf

Jul. 16th, 2025 03:58 pmAaron Taylor-Johnson Will Star in Robert Eggers’ Werwulf

Published on July 16, 2025

Screenshot: Sony Pictures

Share

Delicatessen: A Surreal Apocalyptic Romp About Madness, Morality, and Locally-Sourced Meat

Jul. 16th, 2025 03:00 pmDelicatessen: A Surreal Apocalyptic Romp About Madness, Morality, and Locally-Sourced Meat

Published on July 16, 2025

Credit: UGC

Share

The Bombastic Trailer for the Final Season of Stranger Things Is Here

Jul. 16th, 2025 02:38 pmThe Bombastic Trailer for the Final Season of Stranger Things Is Here

Published on July 16, 2025

Image: Netflix © 2025

Share

The Legend of Zelda Movie Has Found Its Young Stars

Jul. 16th, 2025 02:34 pmThe Legend of Zelda Movie Has Found Its Young Stars

Published on July 16, 2025

Images: Nintendo

Share

Five Science Fiction Books Told in Epistolary Style

Jul. 16th, 2025 02:00 pmFive Science Fiction Books Told in Epistolary Style

Published on July 16, 2025

Photo by Sue Hughes [via Unsplash]

Photo by Sue Hughes [via Unsplash]

Stories told in epistolary format—i.e. via letters, journal entries, or any other written document—are essentially the found footage horror films of the literary world. Not only does this format paint a veneer of realism over the entire story, but it can also feel deeply intimate, with characters often sharing their most private thoughts.

On the flip side, readers can sometimes feel a bit detached from moments of suspense in epistolary stories because the fictional writer clearly got out of whatever sticky situation they’re describing since they’ve survived long enough to write it all down. But there are plenty of examples of stories that either find graceful ways of managing this potential pitfall, finding ways of hooking the reader and weaving a compelling narrative in the gap between the past events and the present account.

Here are five excellent sci-fi books that are told either wholly or largely in epistolary style.

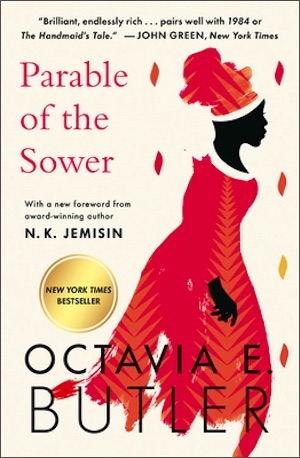

Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler (1993)

Set in a dystopian and post-apocalyptic version of America, Parable of the Sower is composed of the diary entries of teenager Lauren Olamina. Lauren lives in the safety of one of the few remaining gated communities near Los Angeles. Outside the walls is a world that has been ravaged by scarcity. Climate change has led to food and water shortages, unemployment and homelessness are rife, and those in positions of power are dedicated only to increasing their own profits.

When Lauren’s community is destroyed, she heads north with a few other survivors in search of a better life. As well as dealing with the danger posed by roving gangs, Lauren is also attempting to conceal the fact that she has hyperempathy syndrome—meaning that she experiences the pain she sees in others. On top of all of that, she’s also in the process of founding her own religion.

The world Butler crafts in Parable of the Sower is undeniably bleak, but the optimism that pours out onto the pages of Lauren’s diary—she’s certain that things not only can change, but will change for the better—mercifully cuts through some of the misery. The sequel, Parable of the Talents (1998), is also epistolary.

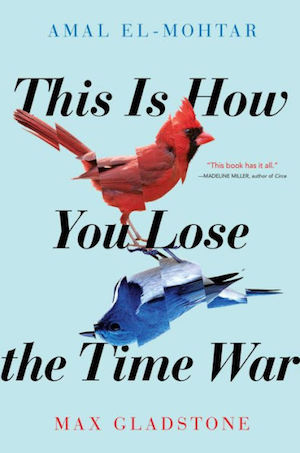

This Is How You Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone (2019)

About half of This is How You Lose the Time War is told through letters, with the other half unfolds as a traditional narrative. The chapters alternate between the POVs of Red and Blue—two agents who are fighting on opposite sides of a war that is conducted via time travel. The story kicks off with Red finding a letter left to her from Blue—essentially bragging about having bested her—and from there, the two enemies strike up an unlikely correspondence as pen pals.

The developing connection between Red and Blue is the core of the novel; any worldbuilding information is essentially drip-fed to readers in tiny bits and pieces, since our two main characters do not need to explain such details to each other. While I found the narrative to be a little confusing to begin with, things soon clicked into place. And from start to finish, the story is crafted in beautifully lyrical language that draws you in, even before the fragments of narrative start forming a satisfying whole.

To Be Taught, If Fortunate by Becky Chambers (2019)

To Be Taught, If Fortunate is written as a direct address to the reader from astronaut Ariadne O’Neill. Along with three other crewmates, Ariadne is on a mission to explore a handful of distant planets that may harbor life. While scientific mission reports have also been sent back to Earth, the words contained within To Be Taught, If Fortunate are the ones that she desperately hopes will be read.

Ariadne essentially tells the tale of their mission. Each planet gets its own section, with Chambers’ wonderfully creative worldbuilding being on full display. But along with the wondrous descriptions of the planets themselves, Ariadne also delves into how she and her fellow astronauts personally react to each new environment—both emotionally and physically, as they terraform themselves to fit the planet, rather than the other way around.

Rather than being an action-packed romp through space, this novella forms a quiet and contemplative travelogue that is imbued with a profound sense of hope.

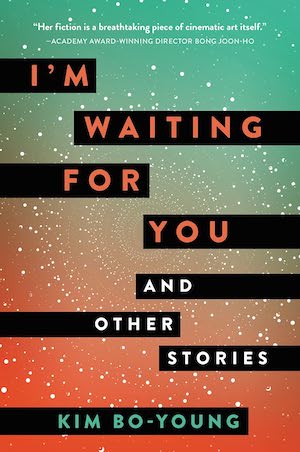

I’m Waiting for You: And Other Stories by Kim Bo-Young (2021)

There are four short stories included in I’m Waiting for You: And Other Stories, but it’s only the first and last stories—the interlinked “I’m Waiting for You” and “On My Way”—that are epistolary. Originally written in Korean, the English translation was done by Sophie Bowman and Sung Ryu.

“I’m Waiting for You” is comprised entirely of letters that an eager groom-to-be has written to his space-faring fiancée. While the trip will pass by in just a few months for her (thanks relativity!), he has to wait years on Earth. Wanting to speed things up, he heads into space himself, but he quickly learns that he should never have messed with time dilation. “On My Way” gives us the other side of the story, in the form of the bride-to-be’s letters to him. These letters reveal that relativity has been just as cruel—or perhaps “uncaring” is more accurate—to her.

Both sets of letters are a perfect blend of deeply personal, heart-wrenching longing paired with a widescale look at the fascinating changes in human development over the course of many years.

Ascension by Nicholas Binge (2023)

Ascension starts with a traditionally told foreword from the POV of the brother of main character Harold Tunmore. Harold is a brilliant, but eccentric, scientist who mysteriously vanished nearly three decades earlier. The rest of the book is told via the letters that Harold sent to his niece while on the ill-fated research expedition that led to his disappearance.

Harold’s letters start off by revealing that he was recruited by a secretive organization to climb and research a huge mountain that had suddenly appeared in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It quickly becomes clear that things are very strange on this snowy mountain, but Harold is driven ever upwards thanks to his scientific curiosity. His letters weave a yarn that is as weird and Lovecraftian as it is action-packed and pulpy.

There are, of course, many more examples of epistolary stories and if you’re after more, check out this list of horror books and this list of short stories told through letters. And, as always, please feel free to leave your own recommendations in the comments below![end-mark]

The post Five Science Fiction Books Told in Epistolary Style appeared first on Reactor.

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds: Rebecca Romijn Teases Genre Jumping Gets Crazier in Seasons 3 & 4

Jul. 16th, 2025 01:30 pmStar Trek: Strange New Worlds: Rebecca Romijn Teases Genre Jumping Gets Crazier in Seasons 3 & 4

Published on July 16, 2025

Photo Credit: Marni Grossman/Paramount+

Share

Read an Excerpt From Mistress of Bones by Maria Z. Medina

Jul. 15th, 2025 07:00 pmRead an Excerpt From Mistress of Bones by Maria Z. Medina

Published on July 15, 2025

Share

Feeling just slightly disingenuous

Jul. 15th, 2025 07:49 pmHave been involved over the last day or so in the discovery and revelation of a hoohah over an esteemed bibliographer having copped to having fabricated a set of letters, of which the transcriptions appear on their website, with, true, a provenance note that might give one to be a tad cautious when citing.

But anyway, someone I know did actually cite something from one of these letters - fortunately not as a major pillar of an argument or anything like that - in their book which is only just published (and copy of which for review I finally received last week). And was informed by the perpetrator.

Cue kerfuffle. The ebook can be readily corrected but not the hardback copies.

But anyway, this led to me (particularly given subject and period) to think upon an instance I had encountered of learning - from the author no less - that a series of supposedly authentic Victorian erotic novels had been knocked up (perhaps that is not the phrase one should employ?) as remunerated hackwork for a paperback publisher in the 1990s.

A few of these are now accessible via the Internet Archive and I discover that they have introductions setting them up as Orfentik Discoveries of the writings of a Private Gents Club.

Anyway, I wrote this all up for my academic blog, and there has been discussion on bluesky about hoaxes and fakes and also I introduced the topic of people being misled by fictional pastiches that were not meant to mislead (or at least, like 'Cleone Knox''s work, have long been known to be made up).

(Ern Malley complicates this like whoa, since it has been claimed that the authors of the hoax actually produced SRS surrealist poetry whether they meant to or not.)

And as a scholar and an archivist I am against hoaxes and fakes and people inserting false documents into archives and so on -

- but I still have the occasional qualm that some naive reader will not read the disclosure of the real origin story right at the back of the volumes and think that the Journals of Mme C-, subsequently Lady B-, actually exist.

Apocalyptic Plagues and Anthropocene Forests: How Charles C. Mann’s 1491 Rewrote My Brain

Jul. 15th, 2025 06:00 pmApocalyptic Plagues and Anthropocene Forests: How Charles C. Mann’s 1491 Rewrote My Brain

Published on July 15, 2025